Recording Havergal Brian’s Cleopatra

by

Lewis Foreman

In the happy days when the late John May’s antiquarian music catalogues were an anticipated regular event, I found myself with endless opportunities to acquire books and scores elusive in even the best music library. Over the years I must have spent hundreds of pounds. One of my greatest prizes from May & May’s catalogues was a mint copy of the vocal score of Havergal Brian’s prize-winning choral work The Vision of Cleopatra, composed in 1907.

Subtitled Tragic Poem for Orchestra, Soli and Chorus (in that order), Cleopatra had been issued by Bosworth & Co. in 1909, to allow its first (indeed only) performance to take place. It was Brian’s entry for the Norwich Triennial Music Festival’s Cantata Competition in 1908. The typographical treatment of the cover and title page would have been very much up-to-the-minute at the time, reflecting the latest Continental views of print design, all Vienna Succession and sans-serif, and underlining how modern it was in its musical treatment. Brian did not win and so his piece was not heard at Norwich, but he did come second, and when his setting was performed it was at the Southport Triennial Music Festival on 4 October 1909. Consequently, he inscribed it to that festival.

At the first performance the orchestra was the Hallé, the conductor [Sir] Landon Ronald. Later, during the Second World War, one of the few significant British publisher’s warehouses to be destroyed during the London Blitz was Bosworth’s, and with it was lost Brian’s unique full score, orchestral parts and probably most of the vocal scores as well. (It is piquant to remember that when Breitkopf & Härtel’s Leipzig warehouse suffered a similar fate in 1944, it was Brian’s mentor and friend Granville Bantock whose music was lost.) It is very difficult music to appreciate at the piano, but the only time we had heard any of Cleopatra was on 8 May 1982 at that year’s Havergal Brian Society AGM when pianist Peter Jacobs played the opening Slave Dance.

I have long thought it possible to rescue Cleopatra if the right person were to undertake the enormous task of re-orchestrating it. Its reappearance, now orchestrated in vivid period style, is thanks to the efforts of composer John Pickard. His realisation is an utterly convincing revelation, and was first heard when he conducted the Bristol University Choral Society and Symphony Orchestra at the Victoria Rooms, Bristol on 12 March 2016.

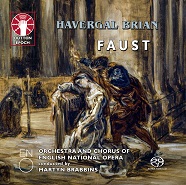

Thanks to the support of the Havergal Brian Society, Dutton Epoch has now taken its Havergal Brian series with Martyn Brabbins back to an earlier time in Brian’s career, with Cleopatra and a supporting programme. A magnificent lineup of young soloists features Claudia Huckle (contralto) as Cleopatra; Peter Auty (tenor) as Antony; the Irish lyric-coloratura soprano Claudia Boyle as Iris; and the mezzo-soprano Angharad Lyddon (who sang Cleopatra at the Bristol University premiere) as Charmion. Martyn Brabbins directed the English National Opera Orchestra and ENO Opera Chorus at Dutton Epoch’s sessions at St. Jude-on-the-Hill, Hampstead Garden Suburb on 5-7 July 2017.

The programme was completed by Brian’s Two Herrick Songs for female chorus and orchestra (1912) – Requiem for the Rose and The Hag (his earliest surviving choral and orchestral pieces) – in a world premiere professional recording. The Concert Overture: For Valour and the Fantastic Variations on an Old Rhyme completed the proceedings. Excluding the Dutton historical Brian programme, this is the fifth disc (the sixth if you include the Cello Concerto, also recorded at St. Jude’s) in Dutton Epoch’s Brian series.

St. Jude’s, Edwin Lutyen’s iconic focus of the Garden Suburb, with its 178-foot spire, is a wonderful recording location for a large-scale work such as Cleopatra, especially in summer. With its hint of the Byzantine, and the murals by Walter Starmer, it seemed a suitable context for Brian’s music, while the entrance directly into the lofty tower transept and the informality of an improvised studio all contributed to the magic of the occasion. The soloists and the choir were under the tower, immediately behind Martyn Brabbins, the orchestra spread out before him in the nave.

The recording took place on three splendidly warm summer days at the beginning of July 2017. At the lunch break on the middle day I was delighted when Martyn Brabbins, John Pickard and the cast agreed to a group photograph outside in the sunshine, which I hope gives a good idea of the spirit and vigour they were bringing to the project.

L-R: Martyn Brabbins, Claudia Boyle, John Pickard, Angharad Lyddon, Peter Auty, Claudia Huckle

The first day was rehearsal. The big day for the soloists in Cleopatra was the second – in fact the first day of recording – but Antony and Cleopatra were also together in the passages not requiring the chorus for much of the third morning. At the very end of the session Claudia Huckle (Cleopatra) glanced up and the sun suddenly caught her face in a quite dramatic way. She was putting her music away, but I dashed over to her and asked if she would hold it while I tried to catch her with my camera, I hope successfully.

These were notably happy sessions, and the soloists and the orchestra impressed all present with their command of such unfamiliar repertoire. The score was sectioned for recording and so there was no complete performance in sequence, but the sections were substantial ones allowing everyone to get a true sense of the music and its underlying drama.

The cast impressed us all; a superbly vibrant group of young professionals all just making their mark in the wider operatic world, and their contributions were fresh and vivid. For example, the Irish soprano Claudia Boyle (singing the role of Iris) was notable for her delivery and vocal colouration before the microphone, remarkably animated in such passages as: “Her proud eyes glanced, Her neck seemed conscious of its loveliness, her lips, curv’d into beauty, parted with the expectancy of lover’s quick pain . . .”

The ENO Chorus were not as large as the student choir at Bristol, but you would not have known it from the sound they made, singing with considerable punch when required, and were also absolutely right in the “small chorus” moments. The women of the choir were miraculously controlled in the Two Herrick Songs, transforming one’s former impression of these atmospheric miniatures.

The session was completed by the two orchestral numbers – For Valour and the Fantastic Variations on an Old Rhyme – in which the playing of the ENO Orchestra under Martyn Brabbins’s direction gave us convincing performances of such natural flow and energy that one was left wondering why both pieces are not in the regular orchestral repertoire.

This programme of the music Brian wrote between 1907 and 1912 reveals that, in his time, Brian was already a composer of real achievement and a distinctive musical personality. It was his tragedy that he could not promote that assessment to his post-First World War audience. In fact, Brian’s command of the latest idioms of his day produced memorable music.

These sessions were a triumph for Martyn Brabbins and his fine orchestra and chorus, and the soloists. In a sense this is also a remarkable discovery for those who are not admirers of the later Havergal Brian – if you love Richard Strauss, Elgar and Bantock then this will be a discovery for you.

Ralph Vaughan Williams: Bluebird, Rhapsodies and Variations

by

Lewis Foreman

Dutton Epoch’s summer 2017 recording sessions with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra and conductor Martin Yates took place in the orchestra’s new hall and offices immediately behind Glasgow’s Royal Concert Hall. The spacious accommodation for the orchestra, the bright summer light and the extremely analytical sound all contributed to a memorable and distinctive session.

Many years ago, the late John Bishop was commissioned by the Vaughan Williams Society to establish a regular journal, and while assembling the first issue (which appeared in September 1994) he asked me to write an article on a VW-related subject that would generate interest and comment. I chose to write about the early and partially lost works of Vaughan Williams, which at that time were generally barred from performance. We were successful, in that my championship of a range of then unheard works was severely criticised by various writers long-associated with the composer. I was unrepentant and as, gradually over many years, we have been able to hear these lost or forgotten scores, it has become apparent that I was right, and the stature of Vaughan Williams has been increased and much lovely music returned to performance, mainly on compact disc.

Such revivals have involved much research in manuscripts and archives to identify what is to be played and how it is to be presented. Dutton Epoch first engaged in this practical research when they recorded John Wilson conducting VW’s impressive 20-minute Heroic Elegy and Triumphal Epilogue (CDLX 7237). However, Dutton Epoch’s expanding engagement with this repertoire came when conductor Martin Yates was introduced to the Vaughan Williams collection in the British Library, and he started to closely study the manuscripts, something that most previous commentators clearly had not done. His succession of wonderful VW discoveries has made his Dutton Epoch series, largely with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, a significant contribution to the Vaughan Williams repertoire.

The 2017 VW session featured more discoveries made in the Vaughan Williams manuscripts. This was a further exploration of what an earlier volume in Martin Yates’s Dutton Epoch series had called “Vaughan Williams early and late works” (CDLX 7289). This time we started with Norfolk Rhapsodies dating back to VW’s folksong-collecting in 1905, followed by his unplayed music for Maeterlinck’s The Bluebird from 1913, and folk-dance settings written for the English Folk Dance and Song Society’s gatherings between the wars, and ended with Gordon Jacob’s orchestration of the Variations for Orchestra (originally for brass band) from the year (1957) before VW died. It made for a fresh, varied and tuneful overview of VW’s achievement, albeit a comparatively unfamiliar one.

Completely unknown, even from many lists of VW’s music, is his score for an episode in Maeterlinck’s play The Blue Bird, which survives in piano score. In 1913 Vaughan Williams wrote incidental music to two plays by Maeterlinck, The Death of Tintagiles and The Blue Bird. The Blue Bird is the most familiar of these plays, but Vaughan Williams’s short score does not seem to have been orchestrated, suggesting, in fact, that it was never performed.

The Belgian playwright Maurice Maeterlinck was all the rage with musicians and the public during the last decade of the nineteenth and the first couple of decades of the twentieth centuries, the most notable score, of course, being Debussy’s opera Pelléas et Mélisande. But many composers wrote incidental music for stage productions, and Vaughan Williams wrote his music in 1913, although the widely-used incidental music, which effectively sidelined VW’s score, was by his friend and colleague Norman O’Neill.

In the years before the First World War, Vaughan Williams wrote incidental music for many plays, including various Greek plays of which The Wasps is the earliest and the most familiar, owing to the popularity of the overture. There were also a variety of Shakespeare plays for F.R. Benson’s 1913 Stratford-upon-Avon season. His music for The Blue Bird presents a series of short fantastic dances comparable to Ravel’s later music in L’enfant et les Sortilèges or Bax’s ballet From Dusk till Dawn.

To hear all three Norfolk Rhapsodies in quick succession was in itself an education. Of course, it shouldn’t have been possible – two pages of No. 2 are missing and the Third Rhapsody is totally lost. Vaughan Williams, enthused by his success in collecting folksongs during winter-time visits to Norfolk in 1905, soon used his memorable discoveries in a variety of orchestral works. We know only the First Norfolk Rhapsody in the 1914 revision, but written in 1906 it was the start of a fascination with these folksongs, and it is said VW was intending to try to turn them into a Norfolk Symphony. The symphony never materialised, but the process he had started, particularly in the later revision of the First Rhapsody, might well be viewed as a kind of technical study for textures and instrumental treatment that later informed his A London Symphony.

The familiar First Norfolk Rhapsody is notable for the atmospheric treatment of the tune The Captain’s Apprentice, given prominence as a viola solo. It was good to find oneself so close to the atmospheric orchestral textures that conjure up the Fenland landscape in winter – this is indeed a landmark in British orchestral music. It came as a bit of a shock to realise that although written in 1906, and the revision first performed in May 1914, the First Norfolk Rhapsody was not published until 1925 and so it did not find a place in most people’s awareness until much later than we might have assumed, looking back.

The second and third Norfolk Rhapsodies date from 1907 and both were heard in the same concert in September that year. Withdrawn by the composer, the Second Rhapsody was long thought unplayable, as two pages had gone missing, that is until Stephen Hogger completed it with reference to the detailed programme notes of the early performances.

When we reach the Third Rhapsody, we are no long hearing a work by Vaughan Williams but the Norfolk March, a tribute by David Matthews based on the original programme notes of a work that is otherwise lost. All enthusiasts who have explored pre-1914 concert programmes will know in what detail the notes are given, in most cases virtually a blueprint for the piece, complete with musical incipits, keys and titles of tunes quoted. We are fortunate that such a note for Vaughan Williams’s Third Norfolk Rhapsody survives from 1907, for when the unique score and orchestral parts vanished during the First World War, it was all that remained.

David Matthews has followed this description in his post-2000 reading. Taking this musical blueprint, David Matthews tells us he has “followed this programme note for the most part as accurately as I could (I begin with a 29-bar introduction in an approximation to Vaughan Williams’s style). The treatment of the four folksongs in the first half of the piece, up to the end of the Trio, with straightforward repetitions in varied scoring, is perhaps more characteristic of Grainger. Up to this point the mood of the piece has been carefree: soldiers marching gaily off to war. But in this centenary of the worst year of the First WorId War, thoughts of what might have happened to those soldiers in 1916 caused me to make a drastic change from what Vaughan Williams would have done. Though I do not stray far from the programme note, the piece becomes suddenly dark and sinister, and the ‘fortissimo and largamente’ statement of Ward the Pirate is a grim funeral march. My coda begins with a wistful recollection of The Lincolnshire Farmer on solo violin, but ending with a kind of ‘last post’ on the trumpets, deliberately recalling Vaughan Williams’s trumpet solo in his Pastoral Symphony, his own First World War statement.”

The craze for open-air historical pageants and masques was a notable feature of the early years of the twentieth century. The Pageant of London in 1911 and the Pageant of Empire in 1924 were notable examples. Although we have a wide familiarity with Vaughan Williams’s espousal of folksong in a variety of oft-played works based on traditional tunes, many collected by VW himself, we have forgotten this inter-war enthusiasm for historical pageants and masques often featuring large groups of amateur singers, where folk music also had a role. The English Folk Dance and Song Society also promoted annual festivals at which Vaughan Williams was usually seen, as he had contributed to the music. Because most of his scores were not published and were often either for military band or idiosyncratic orchestral forces, they have been forgotten. Here, Martin Yates has unearthed a Little Folk Dance Medley, which comes down to us in the original orchestration by Vaughan Williams, the existence of contemporary orchestral parts suggesting it was played at the time. Written in 1934, it may have been for an EFDS event in 1935 (they were usually at London’s Royal Albert Hall). The music features a rapidly changing selection of English country dance tunes, mainly Morris tunes.

A short folksong work left in piano score, so probably never played, was the Little March Suite, in fact a typical short march on folksongs. This folksong quick march is in a familiar Vaughan Williams format, probably best known from the Sea Songs of 1923, music that seems to have been conceived for one side of a 12” 78-rpm disc. Here, Vaughan Williams sets three numbers; the second, On Board a Ninety-Eight, was collected by Vaughan Williams himself during his collecting tour in 1905, when it was sung to him by a fisherman, Mr Leatherby. Another short item that VW orchestrated for performance, but was then forgotten, was his miniature Christmas Overture (1934), another fragment probably associated with the English Folk Dance and Song Society’s annual festivals. This abbreviated Christmas Overture opens with a vigorous presentation of God Rest you Merry Gentlemen, with a middle section presenting the tune Boys and Girls Come out to Play, presumably to illustrate a thematic moment in the event.

In many ways the surprise of the sessions was Gordon Jacob’s orchestration of the Variations for brass band. Vaughan Williams continued writing music to the end and this substantial work appeared immediately before his Ninth Symphony in 1957. It was first performed as the test piece at the National Brass Band Championship at the Royal Albert Hall in October that year, where twenty-one leading bands played it in succession. Hearing it in its orchestral dress was a revelation. I have seen commentators remarking that the band version is more effective; I can only say that with a top-line orchestra such as the RSNO playing it, that is not my experience.

Throughout we find constant reminiscences of this work or that by VW. There are short passages and textures that would not be out place in the Fifth Symphony. The variations are strongly characterised, constantly changing, and the music is always engaging. Gordon Jacob, an old hand at Vaughan Williams’s music, has done an idiomatic job in adapting it from the band to the orchestra. It is full of surprises, for example the fifth variation, which is an increasingly extrovert waltz. The eighth variation, Alla Polacca, is an extended mini-movement running nearly two minutes and announced by a dynamic timpani solo while the strings are silent. Variation ten, a fast Fugato, has the character of a scherzo before the authentic voice of VW closes the proceedings with a typical Chorale. Gordon Jacob surely anticipated how VW would have scored this serene, short finale when he emphasised the strings and woodwind and eschewed the heavy brass until the triumphal closing bars.

John Ireland: A Downland Suite, Julius Caesar, The Overlanders

by

Graham Parlett

On 14 and 15 August 2017 sessions were held in the RSNO Centre, Glasgow, at which Martin Yates – that great champion of British music – conducted première recordings of John Ireland’s complete score for the Ealing Studios film The Overlanders, together with his incidental music for a radio production of Julius Caesar, and Martin’s own arrangement for full orchestra of A Downland Suite. The latter was originally written for the 1932 National Brass Band Championships of Great Britain, and in 1941 Ireland arranged the Minuet and Elegy for string orchestra, his pupil Geoffrey Bush later working on the Prelude and final Rondo in similar style. In arranging the suite for full orchestra, Martin Yates returned to the original brass version and has produced a most enjoyable score that will delight all lovers of John Ireland’s music.

The recording sessions had begun with his impressive music for the Ealing Studios production of The Overlanders, a 1946 film telling the story of real-life events that had taken place four years earlier, when there were fears that the Japanese might invade Australia. This resulted in large numbers of cattle being driven across the Northern Territory from Wyndham in the west to Queensland in the east, a distance of roughly 1600 miles. The film was shot entirely on location there, and although the composer never went to that part of the world it is remarkable how he managed so effectively to evoke its wide, open spaces and to capture the spirit of its people. In 1971, Boosey & Hawkes published a five-movement suite arranged by Charles Mackerras and Two Symphonic Studies by Geoffrey Bush, based on sections from the score but with the original orchestration sometimes altered. For example, the original bass clarinet, tenor tuba and piano parts were either omitted or assigned to other instruments. This recording reinstates the original scoring, and we now have the opportunity of hearing the music complete, including a few episodes omitted from the final soundtrack.

In 1948, the composer had been asked to make a suite from the music but declined to do so, though he later joked about producing a Sinfonia Overlandia to match Vaughan Williams’s Sinfonia Antartica. It is a great pity that he never set about producing such a symphony, as parts of the score, especially in the sections entitled Night Stampede, Mountain Crossing and Water Stampede, contain some wonderfully dramatic music, which were superbly played by the RSNO. This contrasts with Ireland at his most romantic, as in the ravishing Love Theme and in a beautiful section for strings marked “Broad and noble,” with its nod to Tudor music, which links two versions of the recurring passage referred to in the manuscript as the Cheer-up Tune – one of Ireland’s catchiest numbers.

The final score recorded was the incidental music for Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, written for a 1942 radio production and played here, for the first time, complete. It was left to the end of the sessions because it is scored not for full orchestra but for the unusual combination of woodwind, brass, percussion, piano and two double basses. In the manuscript Ireland adds a footnote that the three horns “must do their maximum, & do the duty of 6 players,” and so for the purposes of this recording six horns were used, together with four double basses instead of the two marked in the score. As may be expected, the score includes a number of fanfares and military marches as well as music illustrating several other scenes in the play, such as Ghost Music and Crowd Music. One of the most exciting sections is the Lupercalia Music, used for the scene in which Caesar holds a victory parade during this annual Roman festival and a soothsayer utters the famous warning “Beware the Ides of March.”

There was one section in which Ireland only sketched some music but never finished it, namely the Battle Music, which accompanies the final armed confrontation in October 42 BC between the two principal conspirators (Brutus and Cassius) and Mark Antony. By fleshing out the bare bones of these sketches, it was possible to reconstruct what the composer may have intended if he had had more time in which to complete the scene. As with the other two scores recorded at these sessions, the RSNO players and Martin Yates were on top form and entered wholeheartedly into John Ireland’s memorable music.

All session photos taken by Lewis Foreman

All session photos © Lewis Foreman/Dutton Epoch

Login Status

Login Status