Lewis Foreman reports on Dutton Epoch revivals and musical explorations

Session photographs by the author

Ralph Vaughan Williams: Scott of the Antarctic – the complete score

Arriving in Dundee, on 31 August 2016, for the Royal Scottish National Orchestra’s recording of Vaughan Williams’s complete score for the film Scott of the Antarctic, one was immediately struck by the sight of Scott’s Antarctic research ship Discovery moored alongside the new museum in its name, almost opposite the station. Discovery was Terra Nova’s predecessor, the vessel of Scott’s expedition of 1901-4.

It is a revelation to hear, in sequence, every note that Vaughan Williams wrote late in 1947 for the then unmade Ealing Studios’ film of Scott of the Antarctic. There have been previous attempts to revisit some of the unheard music Vaughan Williams sketched for the film, but now conductor Martin Yates, with the support of the composer’s Estate, has transcribed from the original manuscripts all the music, which comprises some 41 beautifully rounded numbers. In providing this door to all the music Vaughan Williams conceived for the story of Scott and his companions, Yates has achieved something truly remarkable.

Vaughan Williams subsequently reworked some of this material in the Sinfonia Antartica, but to hear his first vivid reaction to the story – before the film was shot – is extraordinary, not least for the speed of its composition (he wrote an hour and twenty minutes of music in the space of just two or three weeks). This epic musical canvas stands independently beside the Sinfonia Antartica as a gripping symphonic experience in its own right.

It is worth reminding ourselves that British film music came of age during and immediately after the Second World War. The groundwork for Vaughan Williams’s achievement had been prepared by considerable activity in the 1930s, and we might, in retrospect, mark out the work of the GPO Film Unit (one of whose luminaries was the young Benjamin Britten) as well as the appearance of a number of notable films.

Possibly the most celebrated British film music before the war was Arthur Bliss’s Things to Come. Although piano arrangements of several numbers from Bliss’s score appeared as sheet music, public interest was only fully engaged by Walton’s Shakespearian scores, the many wartime documentaries with music by all the leading British composers, and such popular 1940s films as Oliver Twist (Arnold Bax), Dangerous Moonlight (Richard Addinsell), The Winslow Boy (William Alwyn), Anna Karenina (Constant Lambert) and Christopher Columbus (Arthur Bliss). British film music’s standing was reinforced by the Daily Mail British Film Festival at the Leicester Square Theatre in 1946, a well-publicised British Film Festival Concert in Prague, Louis Levy’s film music concerts and the BBC’s repeated programming of extracts from various scores.

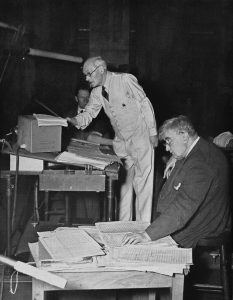

Ernest Irving (on the podium) and Vaughan Williams at the original Scott of the Antarctic recording session

Vaughan Williams was therefore writing for a receptive public, and had started scoring films during the war. He approached Muir Mathieson in 1940, and quickly wrote the music for 49th Parallel, Coastal Command, The People’s Land and The Story of a Flemish Farm. In 1947, Ernest Irving, Music Director of Ealing Studios, asked Vaughan Williams to score the film Scott of the Antarctic. “I believe,” wrote Vaughan Williams, “that film music is capable of becoming, and to a certain extent already is, a fine art … perhaps one day a great film will be built up on the basis of music.” As already mentioned, the writing of his Scott film music was accomplished quickly. By the end of 1947, he had produced a substantial number of separate movements, some in full score – in fact, Vaughan Williams presented the music as a sequence of coherent musical miniatures. And this is all the more remarkable given the extent of the score, which had been written without having seen anything on screen; he worked only from Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s book The Worst Journey in the World, with its haunting photographs, and which in effect served as a draft script.

Vaughan Williams obtained the director’s enthusiastic backing for his approach, which was not to illustrate individual moments in close detail. He was clearly fired by the project; armed with a copy of the script, he went home and set to work. From the dating in Vaughan Williams’s letters, we find that by the time Irving was ready to send him a timed list of the cues requiring music, the score illustrating the composer’s own selection of episodes in the story had already been posted. Irving wrote to Vaughan Williams on 9 January 1948 thanking him for the scores, which he said he “devoured with avidity.” He announced that he would like to record the music at Denham Studios on 6 February, and noting that it included a vocalising soprano, asked the composer to name his preferred soloist – it would be Mabel (later better known as Margaret) Ritchie. In this new recording, Ilona Domnich perfectly catches the required vocal nuance.

Vaughan Williams’s first response to the project came before any of the film was shot. The fact that Irving recorded most of the music immediately means that he had already experienced it live and had it in his head. It also meant that Irving and his staff were able to use a patchwork of extracts of Vaughan Williams’s music as needed. The film music historian John Huntley noted that the composer didn’t seem at all phased when Irving and the production team started to cut the music to the film and found that it fitted.

In a letter to Vaughan Williams, Irving wrote, “Regarding the timings, I am afraid no amount of bullying on my part will produce measurements of film that has not yet been shot.” In fact, the strategy of recording the music so early worked in Vaughan Williams’s favour, as stock colour footage of the panoramic views of the Antarctic was used, and, in some instances it would seem, additional footage was available to accommodate the span of the music. This may possibly be the case in Snow Plain, which runs almost five minutes. Thus, it was possible to argue for the reinstatement of stock colour footage of Antarctica that had already been edited out, which in turn allowed some of the composer’s big set pieces to be used complete. Indeed, it could be argued that the music made the colour footage possible in the cinema.

Typical of the previously unheard discoveries is the lovely pastoral miniature for Oriana, Wilson’s wife. Atmospheric and delicate use of the strings is also notable in the two connected numbers for Scott’s wife Kathleen, as she models a sculpture of her husband’s head (still to be seen at London’s Waterloo Place, below lower Regent Street). Little of her music survived onto the soundtrack, however, and even then is so softly heard as to lose any impact. As a standalone piece, it comes into its own.

In his Scott film music, Vaughan Williams employed an innovative sound palette, especially in the use of percussion including tam-tam, tubular bells, glockenspiel and xylophone. The orchestral piano is also used as part of the tuned percussion, while in the original score recorded here he asked for wind machine, which in the film was replaced by real wind sounds. It was restored when the music was reworked for the Sinfonia Antartica.

In addition to vocalising soprano solo, Vaughan Williams’s score called for women’s choir. Irving was initially worried that the soprano voice might conflict with the dialogue, though in the event the disembodied, ethereal effect caused no problem. We first hear the voices in the second movement, Antarctic Prologue, which in the film appears as a brief atmospheric prologue before the beginning of the story in England is told. Voices later appear in Kathleen 1 (the sculpture scene), Scott and Oates in the Rain, The Death of Oates, and the female choir without solo in the Blizzard. Other features typical of Vaughan Williams’s use of the orchestra include the organ, which adds a pagan power to Aurora 1, the music when they are on the glacier (Climbing the Glacier, Scott on the Glacier and Descending the Glacier) and the final bleak scenes of The Discovery of the Tent and the Bodies and the End Music. Characteristic Vaughan Williams wind solos include the cor anglais in Snow Plain and the rumbustious euphonium in Base Camp.

When Martin Yates and the RSNO recorded the vocal music, the placing in the hall was very effective for those present, the orchestra on the platform and, facing down the hall towards them, the wind machine. Between them was soprano Ilona Domnich and, to her right in the gallery, the women’s choir. It was fascinating to hear live in the hall and is vividly caught in Dutton Epoch’s recorded sound.

Less than half the music that Vaughan Williams wrote was used in the film. The music has become familiar through its later use in the Sinfonia Antartica, the development of which took three years, from 1949 to 1952, and was first heard in Manchester on 14 January 1953.

The scene on Scott’s ship Terra Nova at Cardiff docks (actually filmed at Falmouth) features one atypical number – possibly not by Vaughan Williams – the Queen’s Birthday March, in popular Edwardian style, though there is no credit to another hand. The Terra Nova’s departure features Kathleen and a tearful Oriana standing in the crowd on the quayside, to the strains of Vaughan Williams’s brass harmonisation of Will Ye No Come Back Again, which includes a telling four-bar coda separated from the tune, but unheard in the film. After the ship has sailed, Scott opens a telegram that had arrived as they left, and reads Amundsen’s announcement that he is going south. Vaughan Williams provides a ten-bar cue, unused in the film.

The great strength of Vaughan Williams’s score is in its underpinning of the grandeur and immensity of nature and the ice, together with contrasted episodes featuring the penguins, the ponies and natural phenomena such as the aurora and aphelion (the return of the sun, when the earth is farthest from the sun and the sun smallest in the sky). This, the main musical sequence, with its heroic washes of arpeggiated woodwind and fortissimo brass fanfares leading to the strings’ affirmative melody, is launched by Terra Nova’s departure from Ross Island.

When Vaughan Williams’s complete score is heard in the sequence of the story, it becomes apparent that he had provided the film with a remarkable extra dimension, rather as William Walton had been instrumental in creating much of the impact of Olivier’s Henry V, five years before. But more than that, we now have a vast quasi-symphonic canvas on an almost Wagnerian scale, and in its own way is as satisfying an achievement as the Sinfonia Antartica, which it spawned three years later.

William Walton and Arthur Bliss: Violin Concertos

Dutton Epoch has recorded the Walton and Bliss Violin Concertos with violinist Lorraine McAslan, but using the original orchestration of the Walton, unheard since 1940. The idea of recording the original version of the Walton Concerto originated after comparing the two orchestrations of the Walton Viola Concerto, where the original still has its adherents. When considering the Violin Concerto, one was faced with trying to appreciate the very different orchestration of the first version in the now rather dim sound of its only (78-rpm) recording – in which the commissioning dedicatee, Jascha Heifetz, was the soloist. After the earliest performances, Walton rescored it but without altering the solo part.

So when the proposal to record the first version in modern sound was being discussed, the present writer approached Oxford University Press, was sympathetically received, and visited Oxford to view the score and the original parts. In doing so, it became clear that while the original solo violin part – as published in 1939 – had not changed, Walton had made dramatic changes to the orchestration, reinforcing the romantic nature of the work in the version by which we know it today. Permission was given to record the first version and we are delighted that it is now appearing.

The sessions took place at Watford Colosseum. Presented in the clarity of a Dutton Epoch recording, we can now fully appreciate Walton’s first thoughts, which perhaps are more a reflection of a pre-Second World War musical world. In some places, the orchestration is completely different, while in others the percussion – murky in the original wartime recording – changes; we might feel the loss of the castanets and glockenspiel in the second movement, and gong and bass drum in the third, to be regrettable. Roy Douglas, who prepared many of Walton’s scores for publication, certainly felt that he had gone too far in removing much of the percussion. Now listeners can make their own assessment, with the eloquent violin of Lorraine McAslan and the BBC Concert Orchestra conducted by Martin Yates to guide them.

The Walton and the Bliss Violin Concertos make a compelling programme, and the Bliss Concerto of 1954/55 remains perhaps one of the most impressive British violin concertos not in the day-to-day repertoire. Lorraine McAslan not only underlines its lyrical qualities but also she plays every note – reinstating the minor cuts that are sometimes made.

Hubert Clifford: The Cowes Suite and other works

Australian-born composer Hubert Clifford started his musical career in Melbourne, but came to England in 1930 and remained there for the rest of his career. He started by teaching music in a boys’ grammar school, moved to the BBC as wartime Empire Director of Music and composed much library music for media use, which is still heard today. He became Alexander Korda’s Music Director at London Films. Among other coups, he commissioned zither player Anton Karas for Carol Reed’s film The Third Man, and whose Harry Lime theme went round the world. Clifford later became the BBC’s Head of Light Music.

Although many of Clifford’s later scores have been recorded, a good number of the earlier ones remain unknown, many of which were written in Australia where, in the 1920s, he was a pupil of Fritz Hart. These and his film music have remained in the composer’s original manuscript. We thus started this project with a pile of fading manuscript scores, several bearing the original Melbourne first performance programmes. In association with the composer’s daughter, the present writer contacted an informal team of copyists and arrangers – Graham Parlett, David Bednall and conductor Ronald Corp ‒ who have originated performing materials thanks to the modern miracle of Sibelius software. Also included is what may be Clifford’s last work, The Cowes Suite, commissioned by the BBC and played from printed copies provided by the BBC Music Library.

Clifford was a musician of many parts and this wide-ranging exploration of his art, covering a 30-year span, allows us to hear his tuneful early orchestral works written in Melbourne, including Dargo: A Mountain Rhapsody, a glorious Moeranesque evocation of his childhood home. Two of his film scores, Left of the Line (1944) and Hunted (1952), also receive first recordings. Commissioned by the Canadian Army Film Unit, Left of the Line was written for a documentary about the Canadian forces at D-Day. Ronald Corp has edited the manuscript into a continuous narrative, the music underscoring a succession of comparatively brief episodes on the screen.

Clifford’s music for Hunted, Dirk Bogarde’s first high profile feature, takes us to the black and white world of the early 1950s, in an energetic and emotionally inflected score, the tone set by the arresting title music. In the film, the music consists of discrete numbers often separated by long passages without music. Graham Parlett has edited Clifford’s score into a vivid concert suite.

The Cowes Suite, Clifford’s light-hearted commission for the BBC’s 1958 Light Music Festival, celebrates famous yachtsman Uffa Fox, and provides colourful contrast, completing a tuneful and unfamiliar programme. The BBC Concert Orchestra, originally intended for The Cowes Suite’s first performance, have light music in their veins and throw off Clifford’s music, under the spirited direction of Ronald Corp, in their usual polished style.

Cécile Chaminade: Callirhoë: Ballet Symphonique & Concertstück for piano and orchestra

Conductor Martin Yates pointed out the remarkable qualities of the comparatively few large-scale orchestral works by French composer Cécile Chaminade, best known for her piano miniatures, some of them not quite as easy as many drawing room pianists might have wished. The search for a coupling for Chaminade’s Concertstück Op. 40 for piano and orchestra, and wondering about the four-movement ballet suite from Callirhoë, led to Martin’s discovery of her “ballet symphonique” Callirhoë Op. 37, running nearly fifty minutes. Discovering that both works were premiered in the early spring of 1888, they seemed an obvious coupling.

The complete Callirhoë is a world premiere recording. In fact, it is the first hearing of the complete ballet for very many years – can it really be over a century? – and what a delightful and varied discovery it proves to be; surely a score that needs only to be heard to find producers wanting to see it danced again.

As mentioned, Chaminade has been remembered for her piano miniatures, but pianist Victor Sangiorgio’s brilliant performance in the Concertstück reminds us of what a romantic and affecting composer Chaminade could be when given an extended musical canvas. Sangiorgio’s exhilarating fluency reinforces the image of a French romantic composer at the very peak of her art.

Maximilian Steinberg: Symphony No. 4 Turksib & Violin Concerto

On 21 and 22 June 2016, the Dutton Epoch team were in Glasgow, their first time with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra in the new RSNO Centre at the Glasgow Royal Concert Hall. The RSNO have vacated their long-familiar home, Henry Wood Hall, in the former Trinity Church, where over the years Dutton Epoch has recorded more than 40 CD programmes. It was with the music of Maximillian Steinberg that the bright new hall greeted the Dutton Epoch team.

Steinberg was a pupil of Rimsky-Korsakov – also his son-in-law – in pre-Revolutionary Russia, exhibiting all the orchestral and lyrical characteristics that one might expect from such a heritage. (Steinberg himself would later be a teacher of Shostakovich.) The composer of five symphonies, Steinberg wrote just one instrumental concerto, the unpublished Violin Concerto; his last work, it was completed in 1946, the year of his death.

In the concerto, violinist Sergey Levitin gives a spellbinding performance, seemingly oblivious of the music’s many technical demands. Indeed, Levitin encompasses the virtuosic writing with complete authority while finding its passionate and romantic manner. The concerto’s first movement, unlike the symphony, to quote Guy Rickards’ booklet notes, “is valedictory and autumnal (especially in the central span).” But the music ends with an irrepressible scherzando rounded off, like the symphony, in a sunlit C major. This is a major yet forgotten score by a significant composer of his time.

The Turksib Symphony – Steinberg’s fourth – completed in 1933, celebrates the building of the Turkestan-Siberia Railway.

Using Kazakh folk melodies and in four richly scored movements, it is quite different to the Violin Concerto. This, the acceptable face of Socialist Realism, is a gripping and outgoing score that invites repeated listens. Martin Yates delivers it all with punch and vigour, and the RSNO respond with great panache.

Read More

Login Status

Login Status